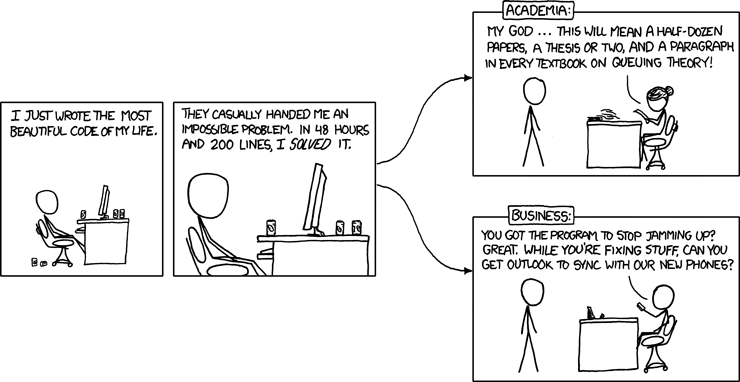

Okay, see that XKCD cartoon up there?

That’s not how law-school academia works.

Law school academia is more like this:

It’s not exactly news that law review articles don’t carry the same weight in their relevant field as, say, scientific papers published in a peer-reviewed journal. Ask any practicing lawyer how many law reviews he subscribes to, and the answer is likely to be “zero.” Ask any practicing lawyer how often he cites law review articles in his motions or briefs, and you are likely to hear either “seldom” or “never.” Ask any practicing lawyer the effect that law review articles have on the practice of law and the advancement of jurisprudence, and he is likely to laugh condescendingly.

It’s not exactly news, but it’s something people have been talking about this summer, after Chief Justice Roberts disparaged the usefulness of legal scholarship at this year’s Fourth Circuit Judicial Conference.

Pick up a copy of any law review that you see, and the first article is likely to be, you know, the influence of Immanuel Kant on evidentiary approaches in 18th Century Bulgaria, or something, which I’m sure was of great interest to the academic that wrote it, but isn’t of much help to the bar.

Law professors, of course, rushed to defend the relevance of their articles. But pointing out that occasionally a law review article might actually get cited in a footnote, to support an argument that was already being made, isn’t quite the strongest defense of relevance.

And it’s foolish for legal academics to make such a defense. Nobody expects them to believe their articles are relevant to actual legal practice any more than one would expect a postmodernist paper in an academic literature journal to be relevant to the publishing industry. Academia and the real life it studies are rarely the same thing.

And it’s foolish for legal academics to even imply that their writings ought to be useful to practicing lawyers. There are only two kinds of law review articles that are of any use whatsoever to lawyers and judges: One is the summary or survey of an area of law as it actually is right now this very moment. The American Criminal Law Review‘s annual survey on white-collar crime is a good example, and there are a fair number of brief summaries of more discrete areas of law as well. The most useful of these are the ones that deal with areas of law that are in flux, describing recent changes, which can help the practitioner or judge test the wind to see which way things are trending.

The second kind of useful law review article is the kind that doesn’t so much restate the law as explain why it is the way it is. These are more rare, but can be very valuable for those trying to make a policy-based argument. A well-done article of this kind takes all the disparate decisions out there and tries to provide an underlying policy that explains most of them. Such a thesis is useful when dealing with an area of the law that is changing, or that one is arguing ought to change.

These useful articles are not useful as something one would cite as part of one’s primary argument. If cited at all, it would be in a footnote. Their value is not as an authority to be cited, but as a guide to help focus or expand one’s own thoughts.

But such articles are few and far between. The overwhelming bulk of law review publications are of little to no use to anyone besides the author.

This is because law review publication does not serve the same purpose as other kinds of academic publication.

-=-=-=-=-

Law reviews serve two purposes: One is to provide an outlet for career academics to publish something — anything — in order to achieve tenure. It’s a pointless exercise, as the quality of one’s articles is of no importance; it is the fact of publication that is important. Having been published often, and recently, is all that is needed to put a check mark in the right box.

The fact of publication is itself no guarantee of the quality of scholarship, that’s for sure. That’s because of purpose number two: To give better law students a way to further distinguish themselves. We do that by having law students pretty much run the show. Students select which articles are published. Students do the fact-checking, making sure the cited sources actually say what the author claims. Students check the grammar, spelling and bluebooking. It’s a lot of work, and shows that one has the ability to juggle responsibilities beyond one’s caseload, and shows an aptitude for the kind of work often assigned to young associates, so it’s fairly prestigious and rightly so. But it is not peer review, and it is no guarantee that the articles themselves are any good. Grammar and cite-checking are not the same as substance.

Neither of these purposes is to provide a useful product for practicing lawyers and judges. So because it is not their purpose, it doesn’t really make sense to knock them when they fail to do it.

-=-=-=-=-

Still, wouldn’t it be nice? You know, if legal scholars were given tenure based on actually contributing something to our jurisprudence? If it was the rule, rather than the exception, for law-review articles to be useful summaries of the law or explanations of the unnoticed policies that explain why the law is and where it is likely to go? Then perhaps one might see them being cited a little more often. Being read by someone not involved in the publication process. Making a difference.

Don’t you want to make a difference?